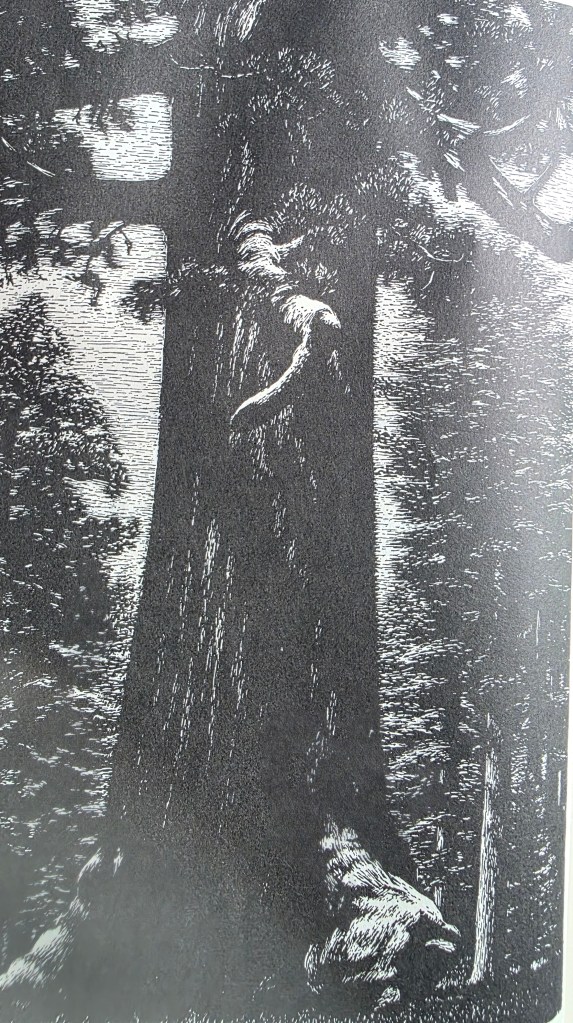

(SCROLL DOWN TO SEE PRETTY ART WORK FROM THIS BOOK)

I got this book out of storage recently. I remember buying it at a bookstore near San Antonio’s Pearl Brewery. It’s printed by Trinity University.

Author Donald Culross Peattie has been dead for decades. In his time he was considered quite the naturalist, you know, someone who studies the natural world, particularly plants, animals, the ecosystems they create, and those systems throughout time.

This books gives brief, scientific yet romanticized explanations of trees across North America. It’s uniquely written. I’ve spent hours with it in my hands.

Now, some of his explanations are excessively stylistic. He can try too hard romanticize trees, and some trees I wouldn’t put on a pedestal.

I personally don’t care much about elms, willows and alders.

Furthermore, I’ve not seen many of the trees Peattie covers. Thus, I’m not terribly interested in Eastern White Pines, Eastern Hemlocks, Ohion Buckeyes, American Chestnuts, Alaskan Cedars, etc.

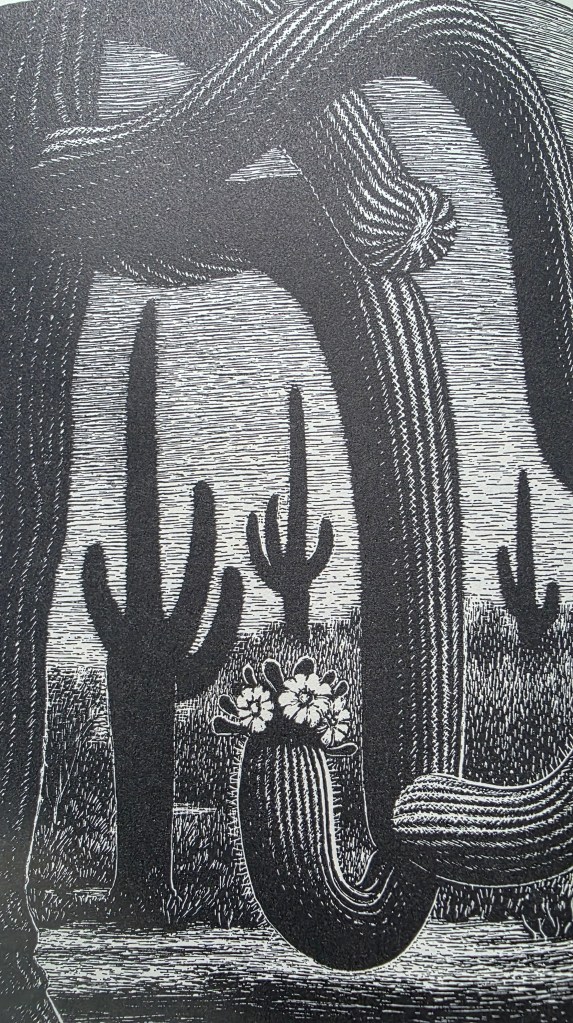

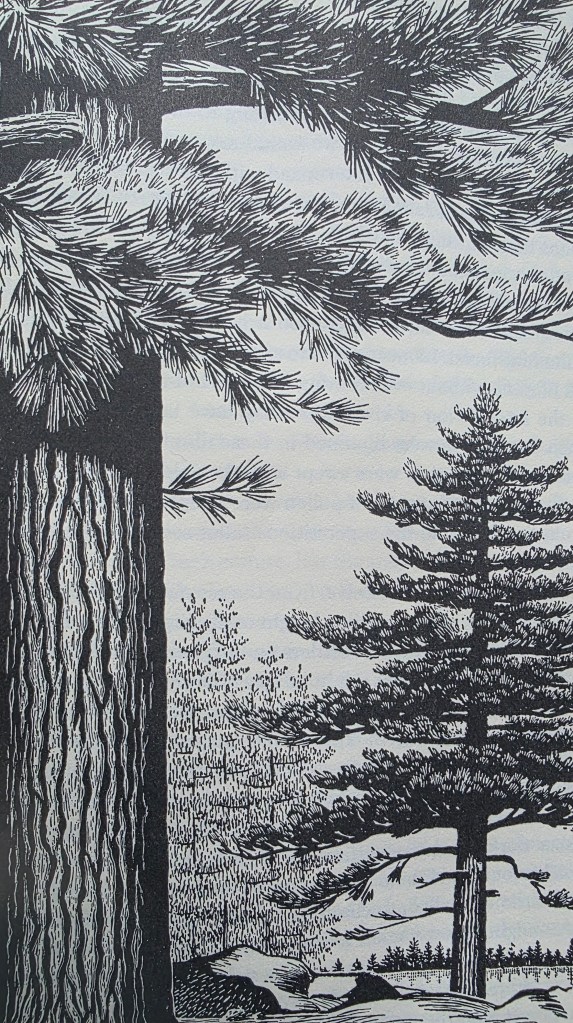

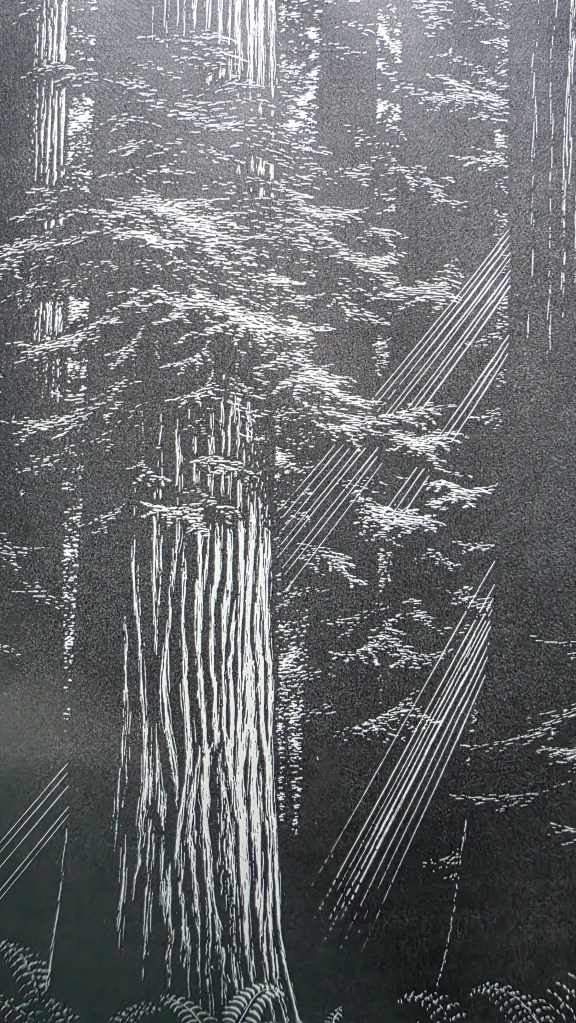

However, Giant Sequoias, Coastal Redwoods, Ponderosa Pines, Colorado Spruces, Douglas Firs, Eastern Red Cedards, Saguaro Cactuses, Desert Palms, and others I do care about. Some I see some a lot. I’ve driven hundreds of miles to see others. After all, why wouldn’t you be curious to see…

The largest trees in the world? The tallest trees in the world? The oldest trees in the world? The highest growing trees in North America? The most widely growing tree in the American West? So on and so forth?

And if you’re curious to see them, why would you not be curious to know something about them? Of course you should!

I mean, if you don’t give the slightest dang about how big sequoias actually are, and the isolated groves in which they grow on California’s Sierras, and elevations they grow at, and when the first white man to see them was, get away from me! YOU ARE BORING.

But seriously, trees are neat because they sort of define the ecology of their environment. They tend to be the dominant species of an ecosystem, and their appearance and disappearance across a landscape are indicative of higher patterns of climate and nature. Alexander Von Humboldt was the first man to really consider patterns of this nature, and Peattie too was a son of Humboldt.

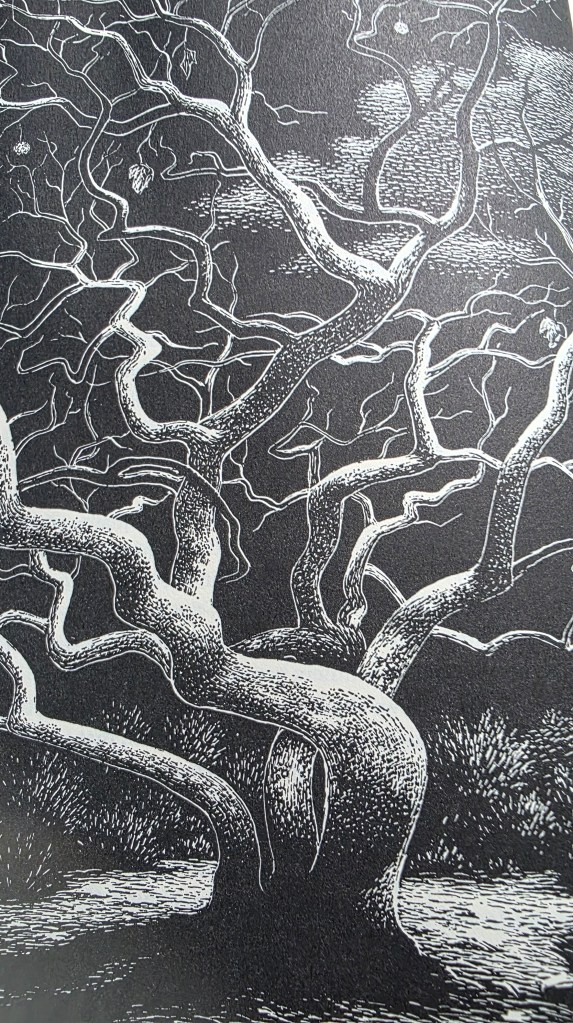

Indeed, Peattie articulates key facts that have jumped out from the pages of this book and caused me to put it down, and stare at the walls contemplating a new concept he just taught me. Pussy willows didn’t do this. But California Redwoods and Monterrey Cypresses did.

And books are at their best when they cause you to do this.

Anyway, one of those recent staring moments involved imagining exploring the first trees of Kansas growing along the bottomlands of streams, and traveling eastward in a circuitous manner to apprehend a composition of the trees of the Great Eastern Forest that dominates North America from the Great Plains to the Atlantic Ocean.

Specifically, it would be interesting to know the changing concentration of tree species from West to East.

It would be interesting to know a thousand other questions I could probably ask along the way, which I will spare you the reader now.

My point is that I may never undertake such a journey in real life, much less count and categorize each species and its concentrations like some 19th century naturalist, the idea is there. It is something to be curious about. It is something to wonder about.

It will make driving through that Great Forest again more stimulating.

Seriously, from planes to prairies to Appalachian highlands, there’s probably some cool patterns to discern if you’re paying attention.

In fact, I guarantee there are.